Changing Business Value Models - How they are having an impact on enterprise architecture

Business Value Models and EA

Commercial businesses exist because they deliver products or services that are valuable or useful to their customers. It is through delivering this value that a business exists and survives. When a company has a strong, differentiating business model it is likely to be more successful. Generating greater value for customers generally leads to greater revenues and profits.

That’s certainly the way that it’s supposed to work. But it’s no good having a great business value model unless it is adequately supported by the right enterprise architecture. Enterprise architecture is the formal description of the components that make up an enterprise, the relationship between those components, and how collectively those components either enable or constrain the management of the organization and the operation of its businesses. The realization of an enterprise architecture is a working, performing system.

Problems arise if there is a mismatch of any sort between the ways in which a business is expected to produce value and the ability of the system described by an enterprise architecture to deliver on those expectations. In other words, a business value model is a great way to look at an enterprise architecture and assess whether it is a “good one” or not. A business value model is also a great input for developing an effective enterprise architecture.

Business Value Models

Let me start by explaining what I mean by a business value model. There are literally hundreds of business models out in the wilds of business management. “Business model” is often a very loose, generic term that covers all sorts of models, such as Michael Porter's Value Chain Model, loyalty models, or the Business Model Canvas. There are various types of business model. Some deal with strategy, some cover marketing, distribution or costs and revenues, while others envelop business operations or organization design.

To make it very clear, I’m going to focus here on models that I’ll call “business value models”; these show how an organization delivers or adds value by explaining the value propositions or configurations of an organization. There isn’t time in this blog to cover more than a couple of types of business value model, but this is OK because the two things I want to point out can be done with some simple examples.

The first point is how important it is to map business value models to the enterprise architecture (both baseline and targets). But the second point is that business value models have changed and are changing – so it is vital to base any changes to the enterprise architecture on contemporary ideas rather than establish outdated ones!

TIP: Explore the business value model(s) for your enterprise. In particular, check to see that the “value” they expect relates to the components, structure and behaviour of the enterprise architecture!

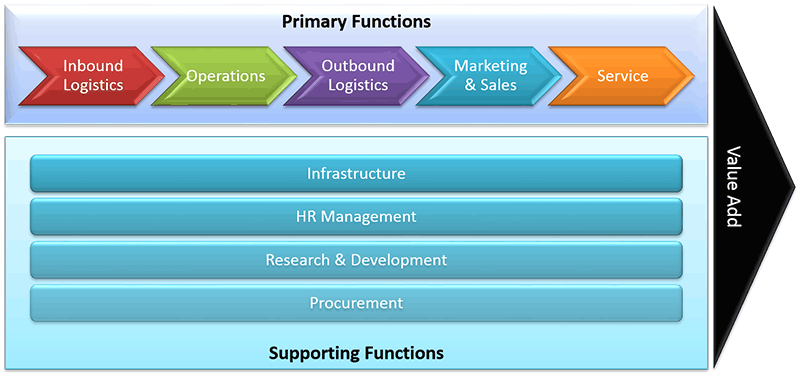

An example of an outdated business value model

Let’s start with a simple example of a business value model that led to misleading requirements and ended up with a poor enterprise architecture. Figure 1 is an example of a Value Chain Model. The ideas behind this model were developed by Michael Porter in the late 1970s, so not surprisingly the model reflects business thinking from around this time. At its most basic, the value chain model shows the key support functions – which are seen largely as overheads or costs, and a primary value chain – which represents a sequence showing the core activities carried out by the company. The core activities or primary functions have costs like the supporting functions, but they also deliver value. In fact, it is this core sequence of functions that produces value and keeps the company in profit.

Figure 1: Michael Porter's Value Chain Model

Our example comes from telecommunications. Business leaders had produced a value chain diagram, similar to the one in Figure 1, which showed the success of the business being dependent on “core” functionality in the underlying communication network. Providing access to this core network to end consumers was seen as the only way to produce value. This thinking was not untypical in the 1980s – for example, providing access to core network functionality lay at the heart of AT&T’s strategy in this period; but this focus also led to its breakup!

Following on strategy discussions based on this value chain, the EA team proposed changes to the enterprise architecture that strengthened the bonds between components that provided access to the core network. For example, they built components to deliver this core functionality, and invested heavily in building these components at the centre of the business architecture layer. Because of the heavy emphasis on the need to develop this core value chain, other parts of the enterprise architecture were often overlooked. For example, there was no effort made to develop capability to share a common network infrastructure or to take advantage of components that were emerging with the growth of the Internet.

The Value Chain model produced a bias towards a single, sequential flow that leveraged in-house functionality and assumed exclusive ownership of the network. It didn’t take into account that possibility that value might be created independently from this central core. For example, it didn’t see the option to create value from an information flow, rather than a functional flow; it didn’t allow for leverage of architectural components that lay outside the boundary of the enterprise.

An example of a more flexible business value model

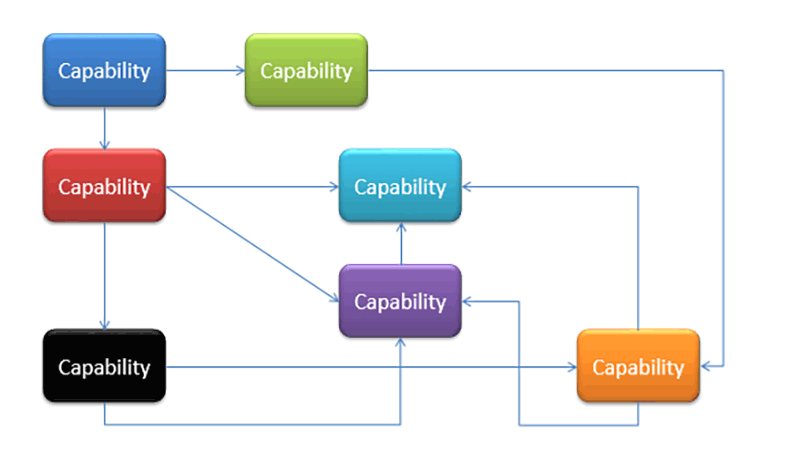

Now let’s take a look at an EA team that used a Capability Map as a way to explore business value with leadership and key decision makers. First of all I need to mention that this is only one technique for examining and modeling business value. If you do a search you will find there are plenty of alternative models available. The important point is to make sure that the business value model being used is one that adequately presents the way that value is currently produced, or the way that the business wants to produce value in the future. You shouldn’t be developing an enterprise architecture based upon it if the business value model doesn’t meet that need!

Figure 2: Dynamic Value - Capability Mapping

In this example, a company delivering online music services wanted a business value model that emphasized the key things that they wanted to do really well, but also showed how they might leverage each capability by combining it with the other core capabilities. A capability map is one way to do this, and in Figure 2 you can see a number of capabilities, with lines showing how value from one becomes an input for building even more value on the next.

Our example company had two sets of customers – people who bought music through them, and people who produced music and wanted to sell it. One capability was the ability to distribute music digitally and via CD through a large range of partner organizations. The company depended on the capability of these partner organizations to do most of its distribution, although it also had its own in-house distribution site. Based on the capability map the EA team identified components to deliver complementary functionality and services that often supported more than one capability. For example, they provided sophisticated search facilities, but added the ability for customers to rate and recommend music, and the ability to guide customers and musicians to related music offerings.

With the Capability Map, value is created independently of whether the architecture components are owned by the central enterprise. Some of the capabilities were also replicated in partner architectures, and some partner architectures provided capability that was central to the value offered by this online music company.

Conclusions

In the early days of enterprise architecture business value models were relatively simple. Most were based around industrial production, with a single, core line of business. Today, business value models are much more varied, and constantly throwing out new ideas and challenges.

Be aware of the changes in business value models. Explore the available models through searches. Talk through business needs with key people to understand which model(s) work best.

If your enterprise is using an outdated model, or you think it could be improved, then have that discussion with key people.

Figure 3: Linking everything to Enterprise Patterns

And above all link any business value model back to the enterprise architecture to show how that either constrains or enables what the business wants to do (Figure 3).

.png)