It’s a fair assumption that anyone seriously interested in the visual presentation of information has heard of Edward Tufte. Businessweek calls him “The Galileo of Graphics”; his courses have been attended by thousands of people over the years. He’s even influenced many leading software packages – for example, Excel 2010 introduced support for the Sparkline graphic named by Professor Tufte. Full disclosure: I have his books.

Now, Professor Tufte’s traditional focus has been on quantitative data, but his focus on clarity of information representation is something that applies to more qualitative analyses as well - such as seen in modeling diagrams such as BPMN or ArchiMate models. The guiding principle that he outlines is that graphics are about conveying information; so anything that does not contribute to this goal needs to be eliminated as a distraction.

I’m going to argue that this principle is valid for models as well. So it’s worth taking a look at whether we can extract any insights into creating more understandable models by adopting the ideas that Tufte outlines.

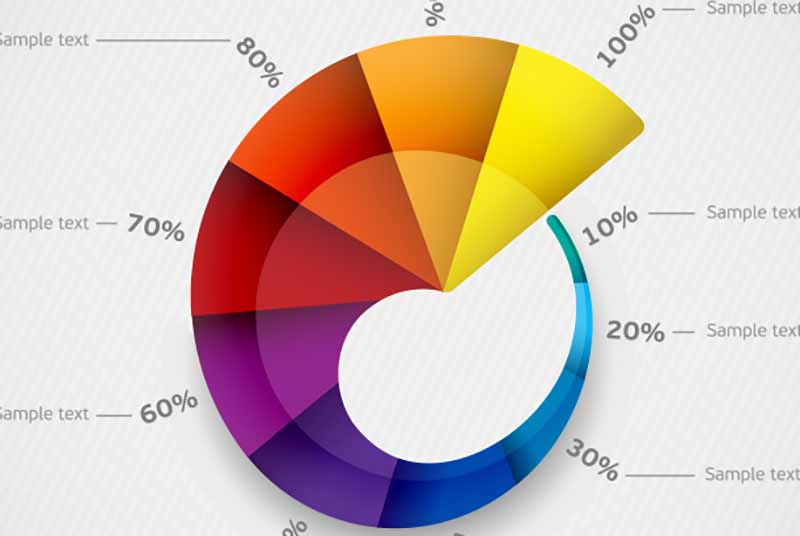

The Data-Ink ratio, clutter and chartjunk

I’ll start with Tufte’s concept of the data-ink ratio. Simply, this is the idea that as much of the ‘ink’ (i.e. visible graphics) as possible should be conveying information. Anything that does not directly convey information should be removed.

A related concept to the idea of the data-ink ratio is what Tufte refers to as chartjunk. Chartjunk are embellishments placed on a diagram to make it look pretty, but which also serve to divert attention from the actual point of the diagram.

At first blush, this might seem to be both self-evident and also irrelevant to models – after all, the notation is usually decided already – but this is not true for two reasons. First of all, for all that the modeling notation may be defined, I’ve seen plenty of modelers add embellishments to make the diagram look less ‘dry’… and the concept of the ‘data-ink’ ratio is saying: “no, the subject is dry. If you want entertainment, go see a movie.”

The second point that makes it relevant is that far too many architecture modelers add in objects that exist, and relate to the items on the diagram, but don’t actually relate to the message of the diagram. To put it another way, your SAP module may well have a data feed from some external system. Is the data relevant to the job performed by the actual project? Is the other system? No? Kill them both, kill them with fire (on the diagram that is).

Recommendation: Only put in embellishments to your models if they explain other elements on the diagram

Recommendation: Only show those objects that relate to delivering the functionality that a given diagram shows.

Completely integrate words, numbers, images, diagrams

The second observation is that Tufte rightly talks about the need to integrate your diagrams, symbols and text. The reasoning is, you cannot guarantee to speak to a diagram – graphics will, sooner or later, be seen by someone in an ‘offline’ context – meaning, where you are not there. What this means in practical terms is that while ideally a diagram should speak for itself. So, annotate your models generously.

Recommendation: Use liberal annotations on your models.

Put structure into the background

The concept here is a simple one; Tufte points out that structural images should be less prominent than the information that they organize. Say for example you arrange information in a grid; under no circumstances should the grid lines be as prominent or more prominent as the lines making up the informational images themselves.

Recommendation: make sure that your borders and connectors don’t outweigh your shapes.

1+1 = 3 or more

The concept here is that information is not just conveyed by the elements on a diagram; their relative positions on the page can convey information. For example, contrast the diagram on the left with the diagram on the right:

Recommendation: space your symbols carefully and use their proximity to one another to convey information.

Avoiding codes

Here the point is that each diagram should stand on its own; it should not rely on looking up information elsewhere to be comprehensible.

Recommendation: Put a legend on each diagram

Conclusions

So – some conclusions from applying Professor Tufte’s principles to modeling then.

- Only put in embellishments to your models if they explain other elements on the diagram

- Only show those objects that relate to delivering the functionality that a given diagram shows.

- Use liberal annotations on your models.

- Make sure that your borders and connectors don’t outweigh your shapes.

- Space your symbols carefully and use their proximity to one another to convey information.

- Put a legend on each diagram.

.png)