War Stories

There are plenty of suggestions out there about how to set up a modeling practice and what you need for one. But in my opinion and experience, gained from working with dozens of practices, some of which have since failed, these guides all omit key items, mainly for reasons of not wanting to seem incredibly cynical. As a blogger subject to less restrictions, I feel able to fill these gaps, and in the next 4 posts I will (cynically) outline the 4 key items that get omitted in descriptions of what a head of practice needs.

The first item that most people forget is war stories. Or perhaps I should say, horror stories.

So, you're newly appointed into the role, and the first thing to be mindful of is the sheer number of skeptics that you face. I wonder if it's even worth stating, but I find that the majority of senior executives can point to a modeling effort that was a waste of time – either in the current organization, or a different one. At the same time, most executives are aware that there are organizations that have realized benefits from modeling, analysis and transformation. The problem is, how do you convince them that you can accomplish the second, and not the first?

There's a simple problem with a lot of the arguments in favor of modeling (whether it’s simply documenting existing systems or transformation efforts). They're abstract. “This process model will ensure that all staff have online access to all the information needed to perform their jobs”. In the USA, they call this 'motherhood and apple pie' – nice warm feeling that no-one can argue with, but...so what?

Contrast this with “we spoke to a dozen people, on average they estimated they each lose a day a year because of asking around trying to figure out how to do a thing. Wish we had a place to see how to do any new task we have to take on”. A little bit more concrete, no?

How about another example that I wrote about long ago, related by their chief architect at the time. State Farm, the US insurer, gave a payments holiday to people affected by Hurricane Katrina. Only problem was, the CEO announced this, just assuming it would be easy to do. It wasn't – fulfilling his promise disrupted operations quite badly.

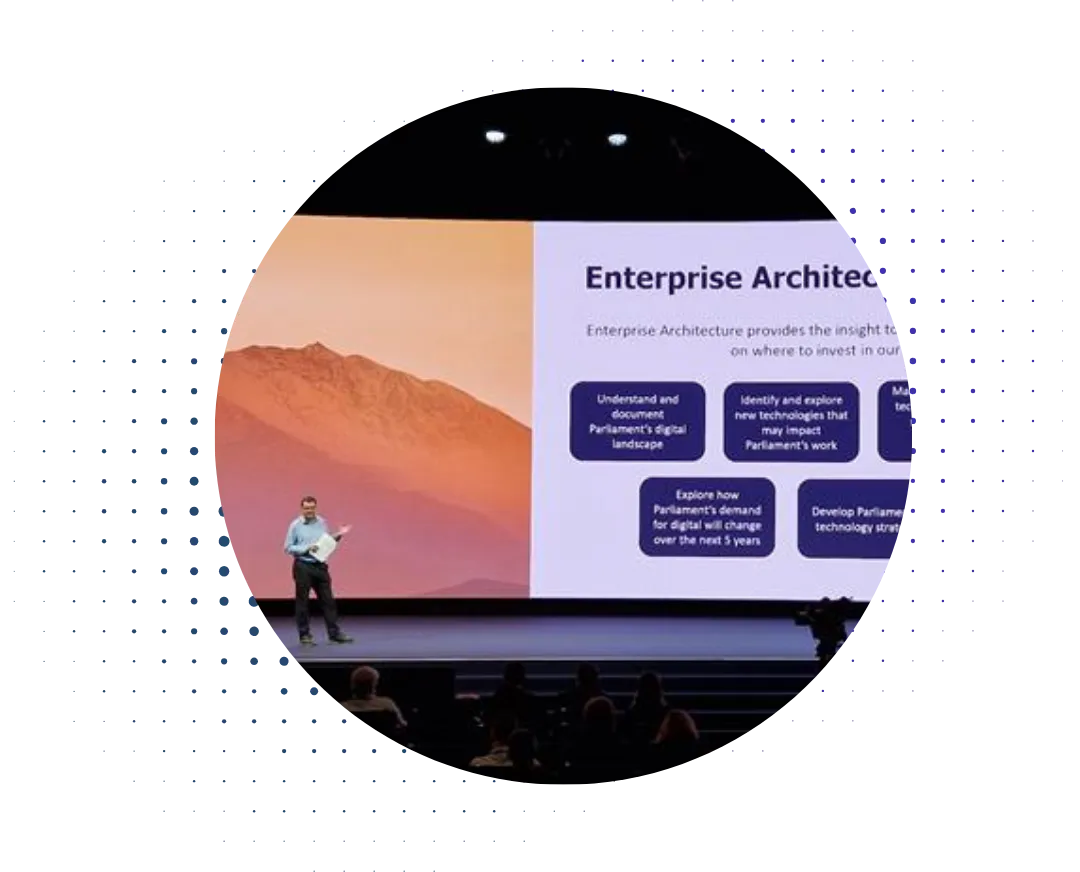

So we can propose the first argument for modeling and then transforming the enterprise architecture - “by mapping and understanding our business architecture, data architecture and technical architecture, we open the door to transforming our business and supporting much better agility in the future”.

Or alternatively - “remember all the pain we went through with Katrina? This is to avoid that happening again.”

It's the nature of people that they'll trust the memory of past problems over future benefits. The pain that they've experience is real. The future benefits may or may not happen. What this means is that reminding people of pain they've experienced in the past, or relating problems that others have had, seems more real than an abstract discussion of business benefits.

There's a saying about sales – “most people don't buy a drill because they want a drill. They want holes”. The same is true of modeling. The organization doesn't particularly want a modeling practice, or to transform its enterprise architecture - it wants to achieve its goals and avoid obstacles to those goals.

So whether you're a newly hired Chief Architect, or just promoted up to set up a process modeling center of excellence, what seems to score according to my observation is the ability to point to historical problems and, most importantly, be able to articulate how these problems get addressed. Even better is if you can quantify these problems into a formal business case (something that we hope to address in a blog series later this year).

War stories. A great article that I once read about sales (by extension, valid for any attempt to convince) said that every pitch had a villain, a monster that you were proposing to slay. Pointing to real life monsters from recent memory, which is to say, recent avoidable crises that you could have averted – it simply feels more real.

Collect horror stories – and use them.

.webp)